7 | Borrowed Forms in Nonfiction

A few pointers on the "hermit crab" essay

A few years ago, I edited an anthology called The Shell Game: Writers Play with Borrowed Forms, a collection of thirty-two “hermit crab essays” (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). What’s a hermit crab essay? you may ask. It’s an essay that, like its namesake, borrows its structure from elsewhere. For example, a hermit crab essay might look like an elaborate grocery list with brief slice-of-life sketches following each food item. Or it might look like a doctor’s prescription pad with information not only about the medications themselves, but also short narratives that, taken together, tell the story of a chronic illness.

Borrowed forms have been around since forever with fiction (think of epistolary novels). But in nonfiction they’re a fairly new development. To borrow a form for use in an essay is to creatively push the limits of nonfiction to the brink—but not breach those limits. The reader must remain confident you’re still talking about reality. For example, if a hermit crab essay uses the first person, the narrator will be identical with the author. That said, one of the great gifts of the hermit crab essay is how it allows for very personal stories to be told in the second or third person, or simply as a presentation of information alone. There’s a gorgeous essay in The Shell Game by Ingrid Jendrzejewski, called “#miscarriage.exe,” that tells the story of the author’s miscarriage in the form of computer script. “#miscarriage.exe” is a deeply personal essay, full of intimate details that anchor it to the author’s real life, but there’s nary a personal pronoun in the entire thing.

I’ve written a number of hermit crab essays over the years as well as two book-length works of nonfiction that use borrowed forms, and, for me, much of the appeal of working this way has to do with the constraints a borrowed form places on the work. Because—paradoxically—once you settle on those constraints, a great sense of possibility and movement opens up within them. In short, writing with borrowed forms can often feel like a form of play.

One of the most popular essays in The Shell Game was written by an 18-year-old high school student named Gwendolyn Wallace. It’s called “Math 1619,” and it’s an essay about being a black girl at a mostly white high school in a mostly white town. Here’s an short excerpt (problem number “3” on the “test”):

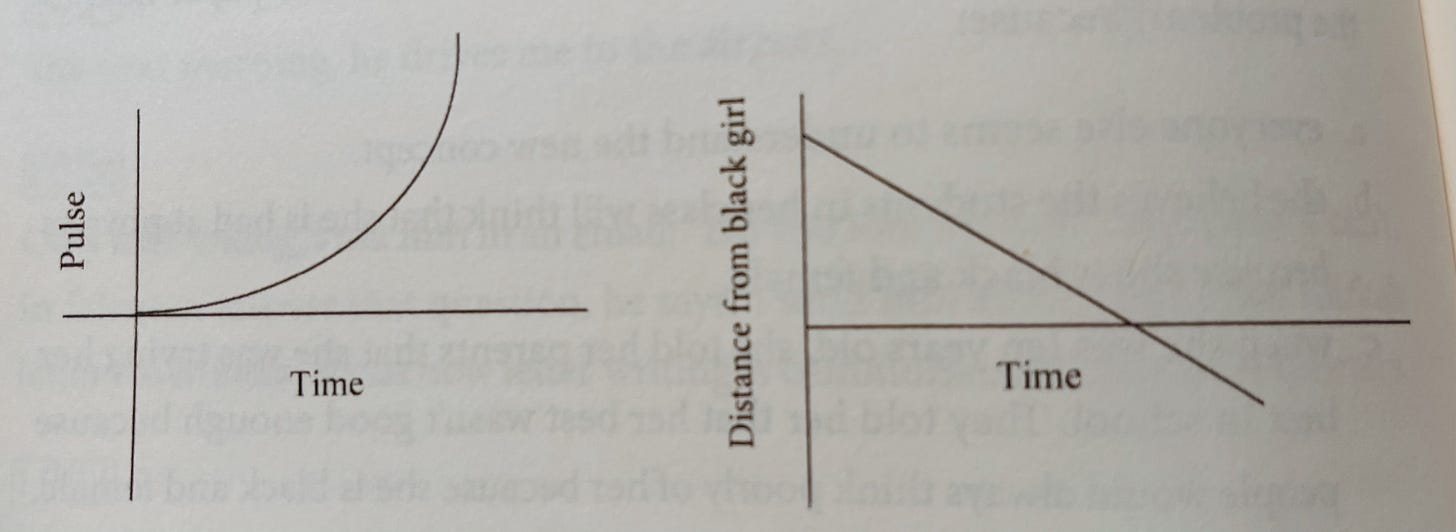

Below is a graph of the black girl’s pulse when she sees the blond-haired woman slowly approach her from behind as she’s buying a Mother’s Day card. This is her first time getting followed in a store. The black girl is in a J.Crew sweater and jeans. The girl remembers to take her hands out of her pockets and slow her breathing. She softens any hardness in her eyes anyone could claim to see. The black girl smiles. The adjacent graph shows how close the saleswoman is getting to her over time. Find the speed of the girl’s pulse when the saleswoman is ten feet away from her.

The form of a successful hermit crab essay works synergistically with its content. One way a well-chosen form contributes to this synergy is by giving the reader an enormous amount of contextual information right off the bat. In “Math 1619” we understand almost immediately that we’re reading about a young, academically engaged black high school student, a girl, who’s grappling not only with the legacy of slavery in the broadest sense (as signaled by the title), but with the much smaller scale, frustrating and often scary racial aspects of authority and power as they show up again and again in her daily life. “Math 1619” is extremely short—only three printed pages. But because the form itself does so much heavy lifting, this brief essay feels big and important.

If you’re curious to try your hand at a hermit crab essay, you might want to keep these tips in mind:

Make your form easily recognizable—otherwise you’ll just baffle your reader. For example, if in your work life you regularly use some kind of specialized form, it may have a lot of personal significance to you, and therefore be a tempting form to borrow, but because it’s specialized, your reader won’t know what it is (unless, of course, you do a lot of explanatory work within the essay itself—which is possible; but as a general rule, it’s best to stick with broadly recognizable forms).

A well chosen form will amplify or echo the central theme or subject of the essay. Think about how the prescription pad example works on a metaphorical level in an essay about chronic illness.

The more rigid the form is, the more it will guide the shape of the essay itself. I once wrote an essay called “Knitting 101” in which I laid out the basic instructions for knitting as an itemized list of twelve pointers for new knitters (e.g. “Materials,” “Anatomy of a Knit Stitch,” “Casting On,” et cetera). Once I’d done that, the essay (which was really about family and domesticity) practically wrote itself because I had such a simple, solid structure, ready to go.

Because of this tendency for borrowed forms to provide fairly rigid structures, a borrowed-form essay can be a terrific way to write about topics that might otherwise seem too small and insignificant—or, conversely, too large and amorphous—or simply too personal and vulnerable to write about in more conventional ways.

Some people like to find an interesting form to work with first; then they seek out an appropriate subject for it. I generally work the opposite way, finding my subject first—something that’s really pressing at me (but that for some reason I find difficult to write about)—before hunting around for an appropriate form. If you want to give this kind of essay a whirl, try both approaches, and see which one works best for you.

If you’re intrigued by hermit crab essays, I hope you find these tips helpful. If you’d like more where this came from, I’m offering a four-hour craft workshop on Saturday, May 21 that will focus on the borrowed form essay. You can read more about the class and register for it here.

As always, thank you for your interest in this newsletter. Please feel free to share it with other writers in your life.

Best of luck finding some interesing shells,

Kim